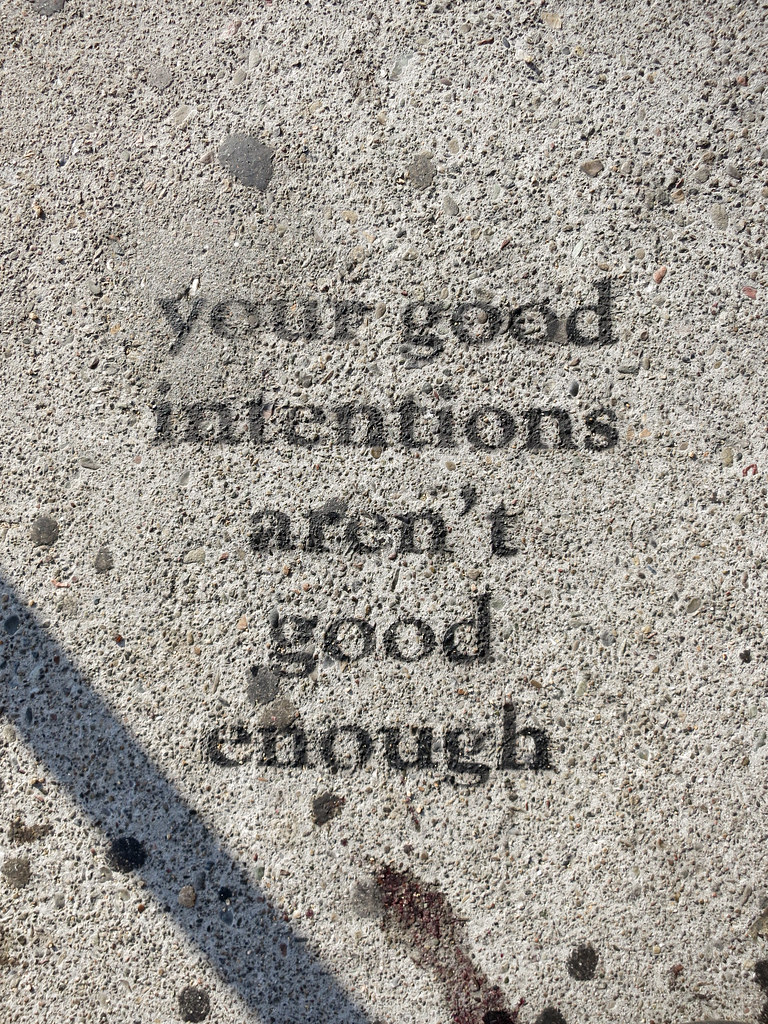

This story begins like many others: with good intentions.

The lesson: Being too trusting of a family member or friend and assuming that you will “work it out” when things go sour (which they almost always do) can ultimately cost you.

The cost: High.

The Story

The story of Mr. A and Mr. R, as played out in the BC Supreme Court recently, is a tale of caution regarding purchasing assets with friends and family.

Mr. A and Mr. R were great friends. They both enjoyed boating. Boats can be expensive, so they came up with a plan: Share the cost of a boat by buying one together. They set out to the Vancouver Boat Show and purchased the Sea Senor for $225,000. They agreed that each of them would be responsible for 50% of the costs associated with the boat including the purchase price.

Unfortunately, Mr. A couldn’t come up with his initial 50% of the purchase price (red flag), but being a good friend, Mr. R agreed to lend him the money at 5% interest.

In order to register the boat, Mr. R and Mr. A created a holding company called Sea-Chariot. Mr. R owned 51% and Mr. A owned 49% of Sea-Chariot. For the next couple of years, sharing Sea Senor worked out for Mr. R and Mr. A. They moored Sea Senor at a Marina close to where Mr. A lived and they split the costs associated with the boat equally.

Unfortunately after a couple of years, Mr. R and Mr. A began to disagree about the repayment terms of Mr. R’s loan to Mr. A. They agreed to sell the boat, but unfortunately they were unable to get what they wanted for it. After they tried to sell it, Mr. R decided that Mr. A had not met the terms of the loan agreement and took action. Without Mr. A’s consent, Mr. R took the boat and, after using it for a time, moved it to another, more remote location.

Mr. A was not happy about this and decided to start a claim against Mr. R. He obtained an order from the court that the boat be “arrested” and it remained tied to dock in the new location. After a trial, the court found that Mr. A was in default of the loan agreement and ordered Mr. A to pay Mr. R $62,000, which he did shortly thereafter. Unfortunately, the trial judge had not made a decision about the sale of Sea Senor, or the costs of maintenance and moorage while the boat was under arrest, so another hearing was required for that purpose. Prior to that hearing, “on the courthouse steps” as they say, the parties reached an agreement, or so Mr. A thought.

The Sea Senor was ultimately sold by Mr. R without the knowledge or consent of Mr. A for $155,000 US. Mr. R deposited the funds into the accounts of Sea-Chariot and then withdrew them. Mr. R then proceeded to send Mr. A a breakdown of the costs he claimed were associated with the boat which purported that Mr. A was entitled to a total of $9.04 from the sale proceeds.

The Cost

Now, litigation is expensive. Mr. A and Mr. R, at this point, had already been through one trial and the post-trial procedures leading up to the alleged settlement agreement. Following those proceedings, Mr. A had been ordered to pay Mr. R approximately $13,000 in costs. Mr. A is left in a difficult position: he must either take the $9.04 that he is being offered, or he must start yet another action against Mr. R (and Sea-Chariot as it was the entity that owned the boat).

Mr. A decides to start another action, this time alleging that Mr. R is in breach of a settlement agreement reached by the parties “on the courthouse steps”. Mr. R denies that there was a settlement agreement, arguing that they had not agreed on all of the essential terms (payment of maintenance and related costs).

To decide whether there was an agreement, the judge had to look at various factors:

- Was there a negotiation? Yes, the parties were asked by the earlier judge to negotiate and did so.

- Did the parties reach agreement (or meeting of the minds) on essential terms? Yes, the parties agreed to the sale of the boat and the payment of expenses; and

- Did the parties act like they had reached an agreement or convey that they had reached an agreement to the outside world? Yes, the parties, through their lawyers, conveyed their agreement to the earlier judge.

The judge found that there was an agreement. The question then became what were the terms of the agreement? Mr. A said that there was a cap on the allowable maintenance expenses Mr. R could be reimbursed for, Mr. R denied there was a cap and said that the parties were going to keep negotiating a cap (noting that a cap was an essential term). The judge did not accept Mr. R’s contention and found that the agreement provided he was entitled to reasonable expenses while the boat was under arrest.

After reviewing the expenses claimed, the judge found that Mr. R was entitled to be reimbursed for $27,850 in expenses that were reasonable. As a result, Mr. A was entitled to approximately $73,850 for half of the sale proceeds.

The judge added yet another cost to Mr. R. Punitive damages are rarely awarded. They are meant as a punishment to a wrongdoer (here Mr. R) for conduct that is “harsh, vindictive, reprehensible or malicious in nature”. An objective is to deter others from acting the same way. The judge was so disappointed with Mr. R’s conduct in breaching the settlement agreement that he awarded Mr. A $5,000.

The Lesson

The lesson in this case is simple: Avoid investments with your friends or family. Sometimes (especially in the current housing market) that is impossible. Your best protection if you’re going to take the unadvised step of buying an asset with your friends or family, make sure you’re all protected. It is easy to say when things are going well and people are happy, excited and hopeful about the future ownership of an asset, that if things go south, he/she/they/you will be reasonable in your dealings with each other. That is always easier said than done. Rather than put your eggs in that basket, it is imperative to use that happy, excited and hopeful energy and put it into a well thought-out agreement (co-habitation for spouses, co-ownership for non-spouses). The agreement will be a god-send when or if you and your family or friend can’t decide whether to sell, or what to do if you do sell, or what to do when a co-owner and their spouse are splitting up.

If you’re thinking about purchasing significant assets, reach out to Cassady Law LLP for a consultation about what you can expect and how to best protect yourself from the cost of a poorly thought-out investment arrangement.